Hi everyone! My name is Marieke de Swart and I am a PhD candidate at the OHE group. We all know that some people are more attractive to mosquitoes than others. I am trying to find out why this is the case for the malaria mosquito Anopheles coluzzii (formerly An. gambiae s.s.). Do people that smell more attractive to mosquitoes have other advantages for this mosquito? Female mosquitoes bite us because they need blood to lay eggs. Can we find something in our blood to explain these differences in attraction? Can mosquitoes smell the person with the blood that will give them an advantage?

Trial with human subjects

To investigate this, I executed a trial with human subjects (from now on, I will say “participants” because that sounds a lot nicer in my opinion). It took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, so it needed some slight changes and creativity to get started. Doing experiments with participants is a strictly regulated process because it falls under the WMO (“wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen” or law for medical scientific human research). In this case, my study was approved by the METC (Medical Research Ethics Committee), an independent group of experts that examines whether the experiment holds up to all research and ethical standards. Among others, they make sure that the payment is realistic and there is no unnecessary discomfort for the participants.

Preparations for participants

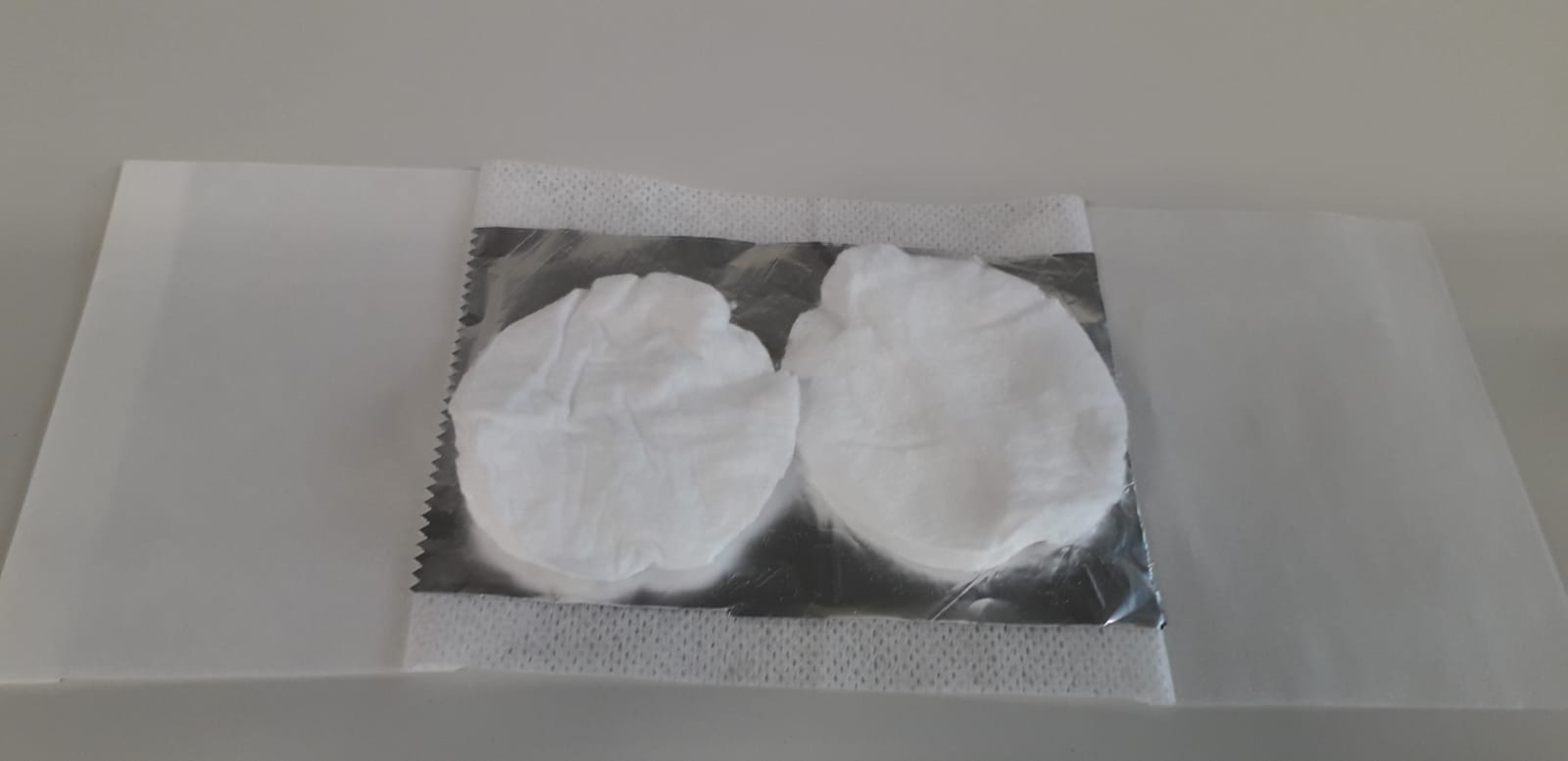

49 healthy men were recruited to participate in this study and join us for a sample visit four times. 48 hours before each visit, they were asked to stop using skin products and only shower with an odourless shower gel to make sure that they smell natural and not of cosmetics. 24 hours before each visit, the participants stopped showering (because sweat is odourless until skin bacteria have the chance to grow and metabolise) and were asked not to eat or drink specific foods like bananas or alcohol because they have been associated with attractiveness to mosquitoes in earlier studies. The night before each visit, they would start wearing an odour plaster: a normal plaster but with two cotton pads placed underneath it on their foot to soak up their odours.

While the participants did their preparations, my assistant Laura and I did ours, such as collecting mosquitoes from our mosquito rearing and labelling all we needed.

Sample collection

The next morning, Laura and I would wait for the participants at the Vaccinatiecentrum on campus where blood of the participants would be collected. We collected blood to feed mosquitoes, but also to look into the amino acid composition and the human immune response. It involved some waiting outside because of the COVID-19 restrictions, so we would hand out some hot tea and chat with the participants until the first group of participants was ready (we always had two groups of five on a day). Then, I’d escort the first group back while Laura waited until the rest was finished as well. We collected the samples in a simple meeting room (large enough for COVID-19 regulations). The participants would take off their odour plasters, take a bacterial sample by rubbing a swab over their foot and feed mosquitoes on their arm.

Blood-feeding mosquitoes

How do you feed mosquitoes by arm? Well, you have probably done it often, just not with the intention to do so. I prepared small buckets with 20 hungry female mosquitoes inside, covered with gauze. This way, you can lay your arm on the bucket (covered with a towel so the night-active mosquitoes were in the dark) and let the mosquitoes come to you. The first time is always tricky because you feel the mosquitoes insert their mouthparts and probe until they find a nice vessel – something you usually never notice! Mosquitoes were allowed to feed for 15 minutes and during this time, lots of questions about mosquitoes would come up, from other mosquito-borne diseases to what my favourite mosquito species was (spoiler: Sabethes cyaneus). These are always really fun to answer! After feeding, you can clearly see the blood-fed mosquitoes. Participants received Azaron (an antihistamine) for some relief against the mosquito bites and some fruit for on the way.

Fully satisfied mosquitoes

As soon as we would have all blood tubes, we would also feed the mosquitoes using an artificial membrane feeding system so we can study differences between blood-feeding from the arm and through an artificial membrane (how important is your skin and are your skin bacteria in the feeding process?). On a day with 10 volunteers, we have a total of 400 mosquitoes that could feed, of which usually around 300 actually fed. We transported every individual blood-fed mosquito in a small glass cuvette and took a picture of the mosquito underneath a microscope camera. This way, we can calculate how much blood the mosquito has ingested, but photographing all these mosquitoes individually surely takes a lot of time.

Checking up

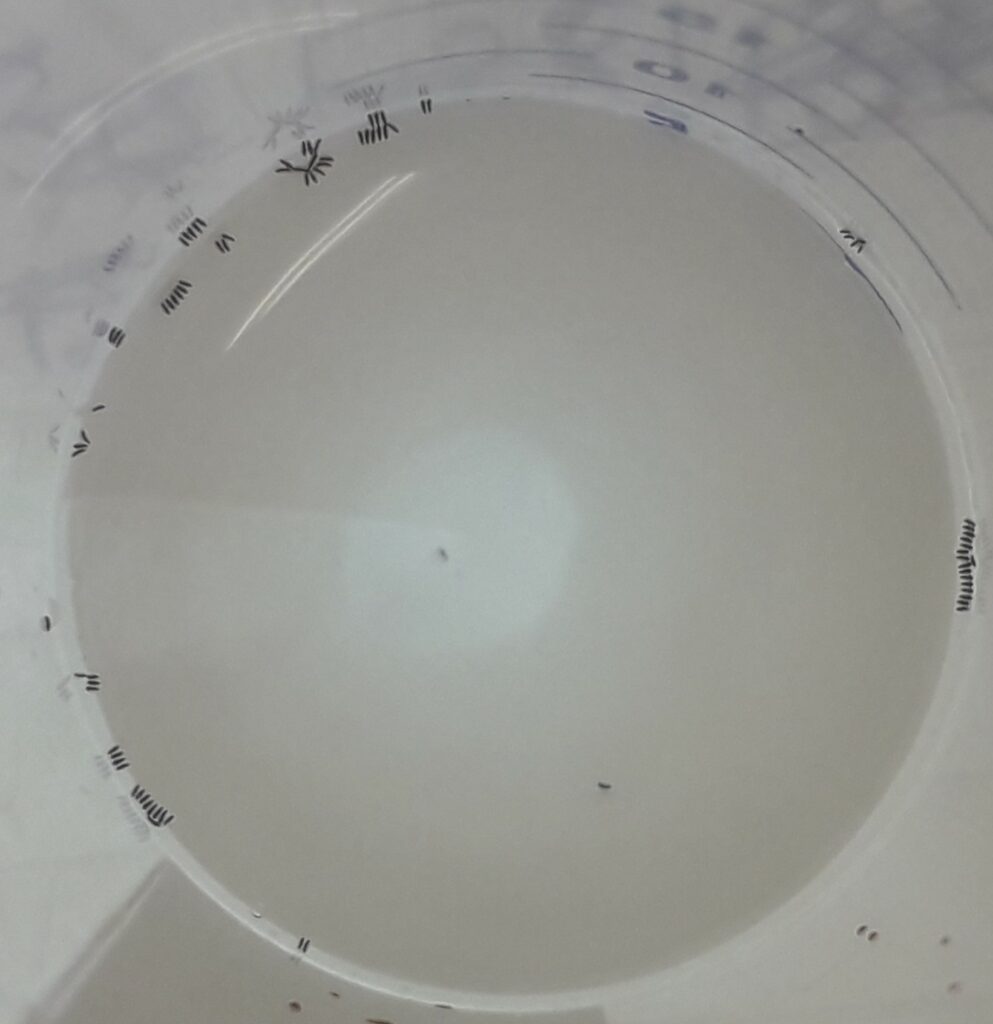

After this, we put each mosquito in her individual 50 ml tube, with some water below for egg-laying and some cloth with a glucose solution placed on top. Mosquitoes naturally feed on nectar from plants, but in our mosquito rearing, this has been standardised with glucose solution. We monitored the survival and egg-laying in every individual tube daily for two weeks.

Now what?

The trial has been completed in March, but there is still a lot to do! Currently, I’m busy counting the numbers of eggs that mosquitoes laid from photos. Apart from that, students and I are testing the attractiveness of the foot odour samples by releasing mosquitoes in a wind tunnel where they can choose to go to a sample worn by a volunteer, or that of a mildly attractive control. Currently, it’s still a lot of data processing and analysing, but hopefully, I can shed some more light soon on why some persons are more attractive to mosquitoes than others.